West Dallas Community School

It takes a special kind of faith and determination to build a school in a neighborhood that has been called the Devil’s Back Door.

Pastor Arrvel Wilson grew up in in the West Dallas projects and dreamed of fleeing. It was for years one of the ten poorest communities in the nation and has the worst high school in Dallas. After serving in the Marines, he felt compelled to return and came back with his wife, Eletha, to start a ministry. He knew that education was vital to saving the community.

“He had been praying for a Christian school in West Dallas,” Cheryl Mayne, Director of West Dallas Community School (WDCS), told ThinkWave. “This community is historically impoverished. The district is mired in poverty. He met other folks that had started a school previously. They had experience in pedagogy.”

Providential meetings with Carole and Norm Sonju (co-founder, former president and general manager of the Dallas Mavericks) and Robin and Michael Lewis, founders of the Providence Christian School, resulted in WDCS.

“They had a network, which gave them credibility as a startup,” said Mayne. “School startups are exceedingly difficult. They were able to start the school in 1995. It was predominantly African-American then.”

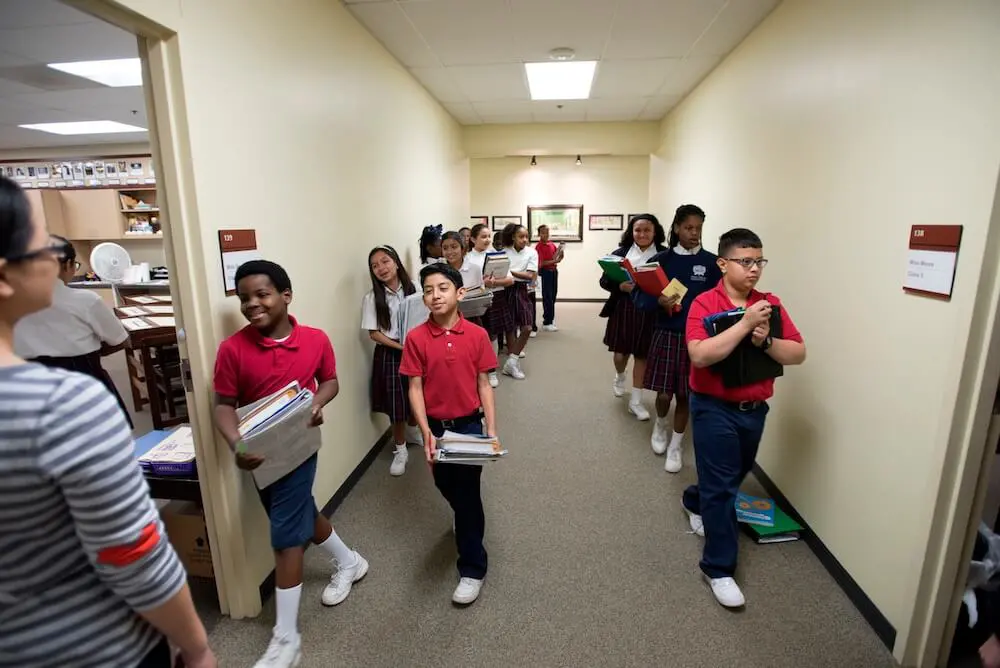

West Dallas’ demographics have evolved. WDCS draws 65 percent of its pre-K-Grade 8 student body from the immediate community, which is now 50 percent Hispanic. Students include children from Dallas’ Asians and Ethiopian refugee communities. The change has brought new issues to the school, which still confronts West Dallas’ core problem.

“Poverty has its own effect on families,” Mayne told ThinkWave. “Many children come from single parent homes, families who have one incarcerated member. We see grandparents raising grandchildren. We see language issues, and not just that children can’t speak English,” she said.

There is a lot of ADHD and oral language deficiencies, said Mayne. WDCS works with Scottish Rite Hospital to treat children with dyslexia.

In order to reach children, WDCS reaches out to families.

“Once a year we go out to the neighborhood,” said Mayne. “If parents are not afraid, we dialogue with them on what we are about. Believe it or not, was are not as well known as you might expect. We have open houses where parents can come to us. We are open to that. There is a lot of word of mouth. People have siblings and cousins and neighbors who are happy with what they have experienced.”

Pastor Wilson’s reputation is a foundation of the school’s success.

“Many trusted the man,” said Robert Hunt, Director of Development. “He said it could be a great opportunity for them.”

Children undergo admissions testing and primary caregivers must play an active role in their education, attending regular meetings and lectures on subjects such as sex education, responsible social media use and conflict management. The caregiver-school relationship is regarded as a partnership and at least minimal tuition is required.

“45 percent of families pay $65 per month,” said Hunt. “Children get a free breakfast and a free lunch from a federal program.”

America may be roiled by curriculum debates, but WDCS’s program is anchored in Classical Christian Education.

“We have three things: classical education, strong humanities, strong math and science,” said Mayne, with “Bible class for students on a daily basis and chapel on Friday led by students and faculty.”

The school’s Christianity is not forced on students.

“We’re not a covenant school,” said Mayne “We are an evangelical mission school. We make it very clear that this is a Christian school,” she said. “We have children whose families are not church attenders, who come to church for the first time. They are influencing their parents. Some of those join churches. Some join churches across the street. We have Ethiopians, who have the Orthodox Church.”

WDCS’s academic program addresses diversity. Eighth graders study the biography of Frederick Douglass and Ben Carson has spoken at the school.

The school’s philosophy is inspired by the ideas of Charlotte Mason, a late 19th-early 20th century British educator.

“She had interesting things to say about how how to interact with children and wrote that each child is a person and not a cog in a machine,” said Mayne. “Each person is created in the image of God and has something to bring to the table both in terms of intuition and intellect. We can learn from children as they respond to beautiful things, from things like a trip outside to learn about leaves. It is important to pay attention to detail.”

Programs with the larger community that foster such interaction include tutoring by volunteers and mentoring by young professionals, all carefully vetted.

“We are looking for mature believers in Christ,” said Hunt. “We see this as a discipleship opportunity. It is a mutually beneficial relationship. We’re not looking for someone coming from a wealthy background to help someone in need. This is an opportunity for both the child and the adult to learn.”

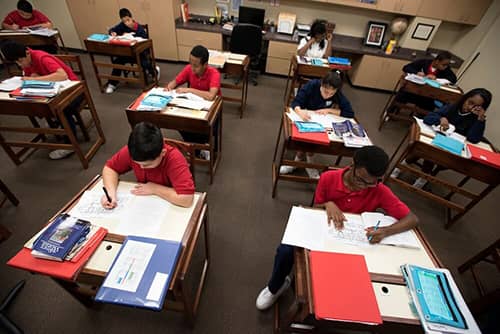

The school aims to place children in high-performing Dallas high schools. Dallas schools have an average class size of 30; at WDCS it is 20-25.

“It is a deliberate choice,” said Hunt. “We see education as the science of relations. If relationships are core to education, we know we will need a smaller classroom. Have relationships with students.”

Hunt leads fundraising efforts to help ensure this goal.

“We are predominantly supported by individuals,” said Hunt. “We have an endowment. We do have a few corporations. Oftentimes our faith-based approach won’t allow them to give to us. We have supporters whose companies allow them to support us. The bulk of funding comes from individuals in Dallas who see us as a benefit to the city.”

Although West Dallas has been getting some positive press as an up-and-coming neighborhood, it remains rough.

“You can throw a stone and hit a house with a rock here, and it will probably fall down,” said Mayne. “On one side of us you can probably see drug trafficking and prostitution. There are inappropriate adult bookstores and video stores. It’s an industrial area that is trying to revive with new restaurants, but there is still a lot of poverty around here. Parents don’t want to send their children to the neighborhood school. Our high school has one student who is college ready. It is still a very desperate place. But right around where we are there has been a ripple effect. You can see our building and our playing field. Now a charter school has gone up as well.”

For the first time, two WDCS alumni have joined the teaching staff. One, Amber Kelley, went to Baylor University; the other, Zach Davis, to Full Sail University in Florida. Other graduates volunteer.

“I was talking to a parent today,” said Hunt. “She had a son named Freddy. When he initially came to school in 2nd grade, he had really low self-esteem. He said he doesn’t fit in in life. The school offers community and a real family of relationships. Freddy each year has grown in confidence in the Lord, as he grew in faith and education. He started to bring this home to Mom and Dad. She said the home has as strong Christian influence now. Before they wouldn’t communicate and tell each other they love one another. So one little child comes in and strengthens his family.”

Freddy is now at a local covenant high school and plans to volunteer at WDCS.

“A lot of our initial students are starting to graduate college and become adults,” said Susan Ervien, Director of Volunteers and Communication. “Our students may take a bit longer. A lot of them have to work through college. We check in with them to see how they are doing in life,” she said. “We want them to succeed in life in general. We want them to succeed in life and faith.”

ThinkWave has simplified staff bureaucracy, improved communication with parents and more effectively channeled efforts of tutors at WDCS, which signed up in 2014. It was easy to implement.

“We had an intern come in and set up calendars and classes,” said Mayne. “This is our second full year of using it.” Mayne’s husband, an IT specialist, discovered ThinkWave during an online search.

“Prior to ThinkWave, we had a cumbersome system for recording grades, a spreadsheet,” said Mayne. “When we developed report cards for students, there was a shared drive. Teachers could only open grades one at a time.”

Mayne said teachers have gained greater flexibility, and everyone benefits.

“We can work from home now, or from Starbucks,” she said “Teachers put their grades in the gradebook and they are imported into a common report card. Because of ThinkWave, we are now able to run weekly report cards. I can run weekly report cards for the intervention team. I can see grades and every missing assignment and communicate assignments. Much to the chagrin of many, we can run reports on academic eligibility for sports. Coaches, students and parents don’t like this, but they know it’s important. We can run them on a weekly basis to know if athletes are eligible to play. If we print them out weekly, teachers don’t have to rush.”

ThinkWave allows teachers to devote more time to students, which is the primary mission of West Dallas Christian School.