THE HILL SCHOOL

How a small town in Virginia built an educational community where teachers and parents are dedicated not only to what students learn but also who they become.

By Kelsey Allen

When Kelly Johnson and her husband were looking for a school for their children, they visited places that promised her third-grade daughter could soon be doing sixth-grade math. Although there are a growing number of parents who want their children to go to a school that starts preparing them for college in kindergarten, the Johnsons were looking for a place where their children could be children.

Then they stepped onto the Hill School campus in Middleburg, Virginia.

Founded in 1926 with a vision to create an educational community where students are the center of attention, the Hill School, for many people, is the community center of Middleburg, population 751. Families have been sending their children to the independent school for generations. But with Washington, D.C., about 50 miles to the east — and growing closer every year — more families are moving to the suburbs, bringing with them a hypervigilance about grades and test scores and succumbing to the pressure to rush their children through life.

Yet the Hill School remains rooted in its philosophy and traditions. “We believe children should have childhoods,” says Hill School Academic Dean Huntington Lyman. “Our children, in a small and supportive community, get the experience of finding their voices.”

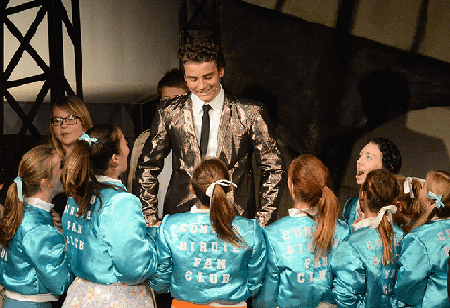

The Johnsons saw first-graders studying bees in the community garden, third-graders reading children’s books in Spanish, fourth-graders learning to play string instruments, sixth-graders rehearsing a class play and eighth-graders competing in a lacrosse match.

“We were looking at our daughter who was really academic and played soccer, but that’s all she did,” Johnson says. “Between 4 and 14, children should participate in everything. They shouldn't have to make choices.

“At the Hill School, everybody in third grade takes a studio art class, writes for a school publication, sings in the choir and plays on a sports team,” Johnson says. “If you don’t allow children to do that — if you just push, push, push — how do they find what their true passion is?”

Johnson’s daughter, Madison, and son, Cole, found their passions — and more — at Hill, and so did Johnson. In 2011, she joined Hill as an admissions and development officer, and today, she is the director of enrollment.

When Johnson talks to prospective parents about the gift of a Hill School education, she shares from personal experience how the faculty and staff’s first concern is to be a family so that students feel supported to explore their own strengths and weaknesses and are challenged to risk succeeding and failing.

By building character, self-confidence and scholarship through co-curricular offerings, place-based learning, individualized attention and a strong school community, the Hill School doesn’t just teach children. It creates lifelong learners.

Using Campus as a Learning Environment

There is a lot that hasn’t changed in the 91 years the Hill School has been open: The educational experience is still defined by three core values: community, character and competence. The class sizes are still small, with enrollment around 235 and most classes being taught in groups of 10 to 15 students. The teachers still build relationships with students that endure beyond their experience at Hill.

But in 1991, the school received a gift that was transformational: Stephen C. Clark Jr. and his daughter, Hill alumna Jane Forbes Clark, gave the school 133 acres of land, increasing its footprint by 3325 percent. Committed to fostering responsible stewardship of the land, the board of trustees and the school leadership set out to create a village-like campus that encouraged a stronger sense of community and allowed faculty to use the outdoor campus as a classroom.

Academic and co-curricular facilities are separated by small courtyards and are connected by a central brick walkway. Students not only get outside when they pass from class to class, but they also walk alongside students and teachers from different grades, allowing upper-school students the opportunity to be leaders and models for younger students.

To help the students develop an understanding of the natural world, the Hill School started a Place-based Education Program. From planting and caring for a pollinator garden to writing a poem about trees in the Hill School Arboretum to learning about colonial gardening methods, the emphasis is on using the physical space as an educational resource.

Educating the Whole Child

John Daum teaches a unit on castles — because what could be more fun for a fifth-grader than that? The fifth-grade homeroom teacher and Culture Study Program co-director also spends four months focusing on the history, architecture, art and culture of New York. His students study the physics behind the Brooklyn Bridge and the history of the immigrants who built it. They learn about Central Park and how it was created to embody democratic values. They research skyscrapers and the technological innovations that make their construction possible. Then he takes the 10-year-olds on a three-day trip to the Big Apple.

“My big goal is to help them see things,” says Daum, who has been at the Hill School since 1997. “I help them understand, particularly with art and architecture, that there is communication happening. The artist is trying to say something to you, and if you can understand what was being communicated and appreciate it, art and architecture become things you can always enjoy no matter where you go. It enriches your life in many ways far beyond Hill School and fifth grade.”

One aspect of developing a lifelong passion for learning is challenging students at an appropriate level of skill and developmental readiness. For math teacher Jack Bowers, that means figuring out where the children are and asking them questions based on that rather than just giving them instructions and grading them on how well they follow them.

“I really try to emphasize that what we do at Hill is provide opportunities for learning from one’s mistakes,” says Bowers, who has been teaching fifth- through eighth-grade math at the Hill School since 1977. “Trying to be perfect is unreasonable. It’s more important to be able to analyze your behavior and the direction you're heading. I really do feel that the community embraces the teachers’ efforts to go beyond instruction and to help their children be good people.”

Engaging Students Throughout the Curriculum

For children to be good citizens and efficient lifelong learners, the Hill School believes they also need to have a sense of worth and belonging. To cultivate that confidence, the school provides an environment in which everyone participates.

Now, not everyone is No. 1, and not everybody gets a trophy. There are varsity and junior varsity teams. There are lead roles and supporting characters in the play. There is a competitive student publication and one that accepts all submissions.

“What that does is, during the course of their week at school, allow every child to experience something that is a natural passion for them and that they’re naturally good at,” Johnson says. “They’re also going to experience some things that don’t come easily to them, but it happens with their classmates and teachers in a loving and supportive environment.”

It’s why Hill School students are not only confident but also empathetic. When Daum’s son and daughter were students at Hill, his daughter would always get blue ribbons for track and field, and his son, who is two years older and more academically inclined, wouldn’t get any. “It builds a sense of empathy when you’ve experienced how hard it is to be weak at something,” Daum says.

But his Hill School family was there to help. A member of the athletics staff designed an individualized program so that Daum’s son could get stronger, and another teacher offered to go running with him after school.

“We’re building young men and women who are going through a process where they really are trying to find their place and learning, at the same time, to support others trying to find their place,” Johnson says.

Promoting a Strong School Community

But none of this is possible without the support of parents.

“Admissions is not about filling seats,” Johnson says. “It’s about bringing in families with a like-minded philosophy who are willing to partner with us in educating their child.”

That partnership begins from the first day students step on campus. Parents new to Hill are invited to a dinner with the board of trustees, and through the Parent-Teacher Club (PTC), they learn about the curriculum and program, hear speakers, and discuss school happenings.

To more efficiently connect administrators, teachers and parents, Hill School started using ThinkWave as its learning management software for fifth through eighth grades two years ago. “I knew we had to make a change,” Lyman says. “We were using different systems for keeping track of grades, maintaining transcripts and generating report cards, and it was getting way too expensive and inconvenient to keep upgrading systems that were all different.”

After researching a variety of systems, Lyman and Silvia Fleming, assistant to the head of school, decided on ThinkWave because the program was affordable, flexible, and easy to learn and use.

“Our teachers now use ThinkWave as their primary grade book, and we print all of our narrative reports on ThinkWave at the end of each trimester,” Lyman says. “We often write extensive narrative reports, and most software programs will not support those long comments. ThinkWave does.”

Lyman has been particularly pleased with the responsiveness of the support team at ThinkWave. "ThinkWave has provided the best support I have found in more than 30 years of working with technology in schools,” he says.

For Hill School, ThinkWave has become an important tool in achieving their mission-driven goal of keeping parents informed about the healthy learning and growth of their children. “ThinkWave helps us keep parents informed,” Lyman says, “and it saves us time to pay attention to what we think is most important in educating children.”